John of Ibelin (jurist)

John | |

|---|---|

| Count of Jaffa and Ascalon | |

| Predecessor | Hugh of Brienne |

| Successor | Guy of Ibelin |

| Born | 1215 Peristerona, Cyprus |

| Died | December 1266 Nicosia, Cyprus |

| Noble family | House of Ibelin-Jaffa |

| Spouse(s) | Maria of Armenia |

| Issue more... | Guy |

| Father | Philip of Ibelin |

| Mother | Alice of Montbéliard |

John of Ibelin (French: Jean d'Ibelin, 1215 – December 1266), count of Jaffa and Ascalon, was a noted jurist and the author of the longest legal treatise from the Kingdom of Jerusalem. He was the son of Philip of Ibelin, bailli of the Kingdom of Cyprus, and Alice of Montbéliard, and was the nephew of John of Ibelin, the "Old Lord of Beirut". To distinguish him from his uncle and other members of the Ibelin family named John, he is sometimes called John of Jaffa.

Family and early life

[edit]His family was the first branch of Ibelins to have their seat in Cyprus, due to his father's regency there 1218–1227.[1] In 1229 John fled Cyprus with his family when Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor seized the Ibelin territories on the island. They settled temporarily in northern Palestine, where the family had holdings. He was present at the Battle of Casal Imbert in 1232, when his uncle John the "Old Lord of Beirut" was defeated by Riccardo Filangieri, Frederick's lieutenant in the east.[2] Around 1240 he married Maria of Barbaron (d. 1263), the sister of Hethum I of Armenia and sister-in-law of King Henry I of Cyprus.[3] In 1241 he was probably responsible for drafting a compromise between the Ibelins and the emperor, in which Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester would govern the kingdom. This proposal was never implemented, and Simon never came to the Holy Land; the Ibelins continued to quarrel with the representatives of the Hohenstaufens, and in 1242 they captured Tyre from their rivals. John participated in the siege.[4]

Participation in the Crusades

[edit]

Shortly thereafter, sometime between 1246 and the beginning of the Seventh Crusade, John became count of Jaffa and Ascalon and lord of Ramla. Ramla was an old holding of the Ibelins, but Jaffa and Ascalon had belonged to others, most recently to the murdered Walter IV of Brienne, whose son John, Count of Brienne (king Henry's nephew) was supplanted by this Ibelin acquisition. This probably occurred when king Henry, John's first cousin, became regent of Jerusalem, and distributed continental lands to his Cypriot barons to create a loyal base there. Jaffa was by now a minor port and Ascalon was captured from the Knights Hospitaller by the Mamluks in 1247.[5]

In 1249 John joined the Seventh Crusade and participated in Louis IX of France's capture of Damietta. Louis was taken prisoner when Damietta was recaptured, but John seems to have escaped the same fate. Louis was released in 1252 and moved his army to Jaffa. Louis' constable and chronicler Jean de Joinville portrays John very favourably; he describes John's coat-of-arms as "a fine thing to see...or with a cross pateé gules".[6] John was by now an extremely famous lord in the east, corresponding also with Henry III of England and Pope Innocent IV, who had confirmed Henry I's grant to John.[7]

Henry I died in 1253, and Louis IX left for France in 1254, leaving John as bailli of Jerusalem. John made peace with Damascus and used the forces of Jerusalem to attack Ascalon; the Egyptians besieged Jaffa in 1256 in response. John marched out and defeated them, and after this victory he gave up the bailliage to his cousin John of Arsuf.[8]

Meanwhile, the Genoese and Venetian trading communities in Acre came into conflict, in the "War of Saint Sabas." John supported the Venetians. In order to bring some order back to the kingdom, John and Bohemund VI of Antioch summoned Dowager Queen Plaisance of Cyprus to take over the regency of the kingdom for the absentee king, Conradin. Nevertheless, the Venetians defeated the Genoese in a naval battle in 1258 and the Genoese left Acre. With Plaisance and Hugh in Acre, the Ibelin family began to decline in importance, but around 1263 John began a scandalous affair with Plaisance, possibly prompting Pope Urban IV to send an official letter in protest, De sinu patris.[9] John's wife and children were believed to have been living apart from him at the time. Maria was visiting her family in Cilicia in 1256 and 1263, and died after visiting her father, Constantine of Baberon, on his own deathbed.

John could do little while Baibars, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, fought with the Mongols in Palestine. Baibars may have reduced Jaffa to vassalage, and certainly used its port to transport food to Egypt. John's truce with Baibars did not last, and he himself died in 1266. By 1268 Baibars had captured Jaffa.[10]

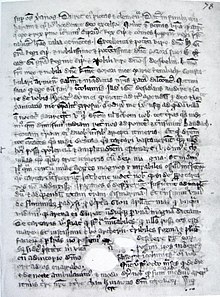

Treatise

[edit]From 1264 to 1266, John of Ibelin wrote an extensive legal treatise, now known as the Livre des Assises, the longest such treatise known from the Levant, dealing with the so-called Assizes of Jerusalem and the procedure of the Haute Cour It also included details about the ecclesiastical and baronial structure of the Kingdom, as well as the number of knights owed to the crown by each of the kingdom's vassals.[11]

Marriage and children

[edit]With Maria of Armenia (sister of Hethum I, King of Armenia and daughter of Constantine of Baberon), John had the following children:

- James (c. 1240– July 18, 1276), count of Jaffa and Ascalon 1266, married Marie of Montbéliard c. 1260

- Philip (d. aft. 1263)

- Guy (c. 1250–February 14, 1304), titular count of Jaffa and Ascalon 1276, married his cousin Marie, Lady of Naumachia c. 1290

- John (d. aft. 1263)

- Hethum

- Oshin

- Margaret (c. 1245– aft. 1317), Abbess of Notre Dame de Tyre, Nicosia

- Isabelle (c. 1250– aft. 1298), married Sempad of Servantikar c. 1270

- Marie (d. aft. 1298), married firstly Vahran of Hamousse, secondly Gregorios Tardif October 10, 1298

Notes

[edit]- ^ Edbury, Peter W. John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Boydell Press, 1997), pg. 34.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 726.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 66-67.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 67-69.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 79-81.

- ^ Joinvile and Villehardouin: Chronicles of the Crusades, trans. Caroline Smith (Penguin, 2009), pg. 276.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 84-85.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 90-91.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 92-96.

- ^ Edbury, pp. 97-98.

- ^ Edbury, pg. 106.

References

[edit]- Amadi, Francesco (1891), Chroniques d'Amadi et de Strambaldi (publiées par M. René de Mas)

- Edbury, Peter W. (1997), John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Boydell Press

- Edbury, Peter W. (2003), John of Ibelin: Le Livre Des Assises, Brill, ISBN 90-04-13179-5

- Nielen-Vandervoorde, Marie-Adélaïde (2003), Lignages d'Outremer, Documents relatifs à l'histoire des Croisades, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, ISBN 2-87754-141-X

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1973), The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174-1277, MacMillan Press

- Rüdt de Collenberg, W. H. (1977–1979), "Les Ibelin aux XIIIe et XIVe siècles", Επετηρίς Κέντρου Επιστημονικών Ερευνών Κύπρου, 9

- Rüdt de Collenberg, W.H. (1983), Familles de l'Orient latin XXe-XIV siècles, Variorum Reprints (Ashbrook)

- Runciman, Steven, History of the Crusades: Volume III, p. 324

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006), God's War: A New History of the Crusades, Penguin Books

- Wedgewood, Ethel (1902), The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville, archived from the original on 2012-03-16, retrieved 2008-11-28