Kalmia latifolia

| Kalmia latifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Kalmia |

| Species: | K. latifolia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Kalmia latifolia | |

| |

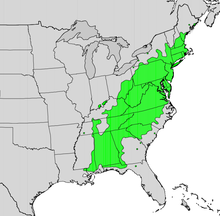

Kalmia latifolia, the mountain laurel,[3] calico-bush,[3] or spoonwood,[3] is a flowering plant and one of the 10 species in the genus of Kalmia belonging to the heath(er) family Ericaceae. It is native to the eastern United States. Its range stretches from southern Maine to northern Florida, and west to Indiana and Louisiana. Mountain laurel is the state flower of Connecticut and Pennsylvania. It is the namesake of Laurel County in Kentucky, the city of Laurel, Mississippi, and the Laurel Highlands in southwestern Pennsylvania.[4]

Description

[edit]Kalmia latifolia is an evergreen shrub growing 3–9 m (9.8–29.5 ft) tall. The leaves are 3–12 cm long and 1–4 cm wide. The flowers are hexagonal, sometimes appearing to be pentagonal, ranging from light pink to white, and occur in clusters. There are several named cultivars that have darker shades of pink, red and maroon. It blooms in May and June. All parts of the plant are poisonous. The roots are fibrous and matted.[5]

-

K. latifolia leaves and early buds

-

Flower buds

-

Beginning to bloom

-

Full bloom

-

Blooming and wilted flowers on the same flower head

-

Bee pollinating mountain laurel on Occoneechee Mountain

-

Kalmia latifolia in North Smithfield, Rhode Island

-

Mountain Laurel fruiting body

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The plant is naturally found on rocky slopes and mountainous forest areas. It thrives in acid soil, preferring a soil pH in the 4.5 to 5.5 range. The plant often grows in large thickets, covering great areas of forest floor. In the Appalachians, it can become a tree but is a shrub farther north.[5] The species is a frequent component of oak-heath forests.[6][7] In low, wet areas it grows densely, but in dry uplands has a more sparse form. In the southern Appalachians, laurel thickets are referred to as "laurel hells" because it is nearly impossible to pass through one.

Ecology

[edit]Kalmia latifolia has been marked as a pollinator plant, supporting and attracting butterflies and hummingbirds.[8]

It is also notable for its unusual method of dispensing its pollen. As the flower grows, the filaments of its stamens are bent and brought into tension. When an insect lands on the flower, the tension is released, catapulting the pollen forcefully onto the insect.[9] Experiments have shown the flower capable of flinging its pollen up to 15 cm.[10] Physicist Lyman J. Briggs became fascinated with this phenomenon in the 1950s after his retirement from the National Bureau of Standards and conducted a series of experiments in order to explain it.[11]

Etymology

[edit]Kalmia latifolia is also known as ivybush or spoonwood (because Native Americans used to make their spoons out of it).[12][13]

The plant was first recorded in America in 1624, but it was named after the Finnish explorer and botanist Pehr Kalm (1716–1779), who sent samples to Linnaeus.

The Latin specific epithet latifolia means "with broad leaves" – as opposed to its sister species Kalmia angustifolia, "with narrow leaves".[14]

Despite the name "mountain laurel", Kalmia latifolia is not closely related to the true laurels of the family Lauraceae.

Cultivation

[edit]The plant was originally brought to Europe as an ornamental plant during the 18th century. It is still widely grown for its attractive flowers and year-round evergreen leaves. Elliptic, alternate, leathery, glossy evergreen leaves (to 5" long) are dark green above and yellow green beneath and reminiscent of the leaves of rhododendrons. All parts of this plant are toxic if ingested. Numerous cultivars have been selected with varying flower color. Many of the cultivars have originated from the Connecticut Experiment Station in Hamden and from the plant breeding of Dr. Richard Jaynes. Jaynes has numerous named varieties that he has created and is considered the world's authority on Kalmia latifolia.[15][16]

In the UK the following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

- 'Freckles'[17] – pale pink flowers, heavily spotted

- 'Little Linda'[18] – dwarf cultivar to 1 m (3.3 ft)

- 'Olympic Fire'[19] – red buds opening pale pink

- 'Pink Charm'[20]

- Some cultivars

-

'Clementine Churchill' in the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid

-

'Little Linda'

-

'Minuet' in Christchurch Botanic Gardens

-

'Olympic Fire' in the Dorothy Clive Garden, England

-

'Pinwheel' in Brookside Gardens, Maryland

Wood

[edit]

The wood of the mountain laurel is heavy and strong but brittle, with a close, straight grain.[21] It has never been a viable commercial crop as it does not grow large enough,[22] yet it is suitable for wreaths, furniture, bowls and other household items.[21] It was used in the early 19th century in wooden-works clocks.[23] Root burls were used for pipe bowls in place of imported briar burls unattainable during World War II.[22] It can be used for handrails or guard rails.

Toxicity

[edit]Mountain laurel is poisonous to several animals, including horses,[24] goats, cattle, deer,[25] monkeys, and humans,[26] due to grayanotoxin[27] and arbutin.[28] The green parts of the plant, flowers, twigs, and pollen are all toxic,[26] including food products made from them, such as toxic honey that may produce neurotoxic and gastrointestinal symptoms in humans eating more than a modest amount.[27] Symptoms of toxicity begin to appear about 6 hours following ingestion.[26] Symptoms include irregular or difficulty breathing, anorexia, repeated swallowing, profuse salivation, watering of the eyes and nose, cardiac distress, incoordination, depression, vomiting, frequent defecation, weakness, convulsions,[28] paralysis,[28] coma, and eventually death. Necropsy of animals who have died from spoonwood poisoning show gastrointestinal hemorrhage.[26]

Use by Native Americans

[edit]The Cherokee use the plant as an analgesic, placing an infusion of leaves on scratches made over location of the pain.[29] They also rub the bristly edges of ten to twelve leaves over the skin for rheumatism, crush the leaves to rub brier scratches, use an infusion as a wash "to get rid of pests", use a compound as a liniment, rub leaf ooze into the scratched skin of ball players to prevent cramps, and use a leaf salve for healing. They also use the wood for carving.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Stritch, L. (2018). "Kalmia latifolia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T62002834A62002836. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T62002834A62002836.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0 - Kalmia latifolia". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Kalmia latifolia". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Stich, Kelly (2021-06-11). "How the mountain laurel became Pennsylvania's state flower". Pennsylvania Wilds. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 186–189.

- ^ The Natural Communities of Virginia Classification of Ecological Community Groups (Version 2.3), Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, 2010 Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schafale, M. P. and A. S. Weakley. 1990. Classification of the natural communities of North Carolina: third approximation. North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation.

- ^ "Planting Guides" (PDF). Pollinator.org. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ McNabb, W. Henry. "Kalmia latifolia L." (PDF). United States Forest Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Nimmo, John R.; Hermann, Paula M.; Kirkham, M. B.; Landa, Edward R. (2014). "Pollen Dispersal by Catapult: Experiments of Lyman J. Briggs on the Flower of Mountain Laurel". Physics in Perspective. 16 (3): 383. Bibcode:2014PhP....16..371N. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0141-9. S2CID 121070863.

- ^ Nimmo, John R.; Hermann, Paula M.; Kirkham, M. B.; Landa, Edward R. (2014). "Pollen Dispersal by Catapult: Experiments of Lyman J. Briggs on the Flower of Mountain Laurel". Physics in Perspective. 16 (3): 371–389. Bibcode:2014PhP....16..371N. doi:10.1007/s00016-014-0141-9. S2CID 121070863.

- ^ Harris, Tony (11 August 2015). "Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia)". mycherokeegarden.com. WordPress. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ "Kalmia latifolia". missouribotanicalgarden.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Harrison, Lorraine (2012). RHS Latin for Gardeners. United Kingdom: Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 978-1845337315.

- ^ Shreet, Sharon (April–May 1996). "Mountain Laurel". Flower and Garden Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-05-26.

- ^ Jaynes, Richard A. (1997). Kalmia: Mountain Laurel and Related Species. Portland, OR: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-367-4.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Kalmia latifolia 'Freckles'". Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Kalmia latifolia 'Little Linda'". Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder – Kalmia latifolia 'Olympic Fire'". Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector – Kalmia latifolia 'Pink Charm'". Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Species: Kalmia latifolia". Fire Effects Information Service. United States Forest Service. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Mountain Laurel". Wood Magazine.com. 2001-10-29. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ Galbraith, Gene (September 12, 2006). "The legacy of the Ogee Clock". Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Mountain Laurel". ASPCA. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ Horton, Jenner L.; Edge, W.Daniel (July 1994). "Deer-resistant Ornamental Plants" (PDF). Oregon State University Extension. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-29. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Kalmia latifolia". University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Grayanotoxin". Bad Bug Book. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. May 4, 2009. Archived from the original on March 14, 2010. Retrieved Oct 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c Russell, Alice B.; Hardin, James W.; Grand, Larry; Fraser, Angela. "Poisonous Plants: Kalmia latifolia". Poisonous Plants of North Carolina. North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04. Retrieved Oct 3, 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Linda Averill 1940 Plants Used As Curatives by Certain Southeastern Tribes. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Botanical Museum of Harvard University (p. 48)

- ^ Hamel, Paul B. and Mary U. Chiltoskey 1975 Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History. Sylva, N.C. Herald Publishing Co. (p. 42)

External links

[edit]- IUCN Red List least concern species

- NatureServe secure species

- Kalmia

- Flora of the Appalachian Mountains

- Trees of Northern America

- Natural history of the Great Smoky Mountains

- Plants used in traditional Native American medicine

- Plants described in 1753

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

- Symbols of Connecticut

- Symbols of Pennsylvania

- Garden plants of North America